How Chinese Food in America Has Defied the Odds of History

How Chinese Food in America Has Defied the Odds of History - Menuism Dining Blog, July 22, 2019

With something in the neighborhood of 50,000 Chinese restaurants in the United States, Chinese food is one of the most popular types of ethnic food here. Indeed, Chinese restaurants outnumber the 14,000 McDonalds locations, and even the top five fast food outlets combined. Towns with as few as 1,000 residents sport a Chinese restaurant.

The popularity of Chinese food in the United States is a testament to the popularity of the food itself. But when you consider all of the obstacles that had to be overcome, from the Chinese Exclusion Act to racial discrimination, from boycotts to legislation backed by labor unions, the endurance of Chinese food is also stunning.

The barriers to today’s success of Chinese restaurants fell into two categories: those placed on the Chinese American community in general, and those specific to Chinese restaurants.

Barriers to the Chinese American community

The Chinese Exclusion Act (1882)

The Chinese Exclusion Act was the most significant influence on the Chinese American community, as it prevented most Chinese from immigrating to the United States between 1882 and 1943. Until the law’s enactment, the United States had never restricted immigration (aside from criminals and those with diseases), earning the act an ignominious distinction. The Chinese Exclusion Act reduced the Chinese population in America from a peak of perhaps 300,000 to below 100,000 by 1920.

Hostility in America

Meanwhile, the Chinese still living in the United States suffered all forms of discrimination. The Chinese fared no better than other minorities of color in housing and school segregation to social and economic discrimination.

As late as the 1940s, most Chinese could find employment only within ethnic Chinatowns, in laundries, or as domestic help. It was unheard of to employ Chinese workers in private industry.

Even in the Los Angeles area, the Chinese were subject to “sunset” laws. “Sundown towns” like Glendale, South Pasadena, and Hawthorne prohibited the presence of people of color within city limits after sundown.

In many jurisdictions, real property ownership and employment in certain occupations were limited to U.S. citizens, at a time when the Chinese were ineligible for naturalization. And whether alien or citizen, Chinese were barred from ownership of properties that contained racially restrictive covenants in them.

How Chinese restaurants survived

Despite the hostile environment for Chinese Americans, starting in the 1890s, white Americans started to patronize Chinese restaurants. Conveniently, they made up for the steady decline of Chinese diners wrought by the exclusion laws, enabling the restaurants to stay afloat.

The white diners who began to venture into Chinese restaurants initially were mostly adventuresome, “Bohemian” slummers. They created a late-night scene that drew many outsiders into the exotic “chop suey houses.” After the turn of the 20th century, Chinese restaurants also went more mainstream, with large and nicely decorated restaurants that served a combination of Chinese and American food. Well patronized fine-dining Chinese restaurants opened in Manhattan Chinatown, such as Chinese Tuxedo, Chinese Delmonico, and Port Arthur, as well as throughout Manhattan itself.

Barriers to the Chinese restaurant industry

Union boycotts

By the late 1800s, Chinese restaurants proved to be too successful. Using a variety of tactics, including exaggeration and disinformation, America’s labor unions began a campaign

to stamp out the unwanted, non-unionized competition. The anti-Chinese

restaurant campaign kicked off in earnest with the now-infamous essay

written by labor icon Samuel Gompers (later immortalized on a United

States postage stamp), “Meat vs. Rice, American Manhood Against Asiatic Coolieism, Which Shall Survive?”

Union boycotts followed, both of Chinese restaurants, as well as non-Chinese restaurants that sought to employ Chinese workers. Though the boycotts occurred in many cities and were promoted on the national level by labor unions, they had little effect on the patronization of Chinese restaurants in the long run.

The pervasive idea that Chinese men were a threat to white women

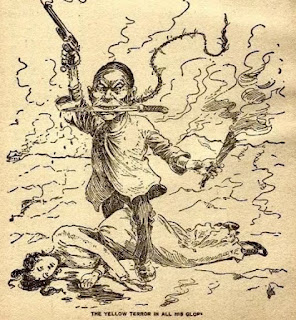

Labor unions took a more emotional approach to discredit Chinese restaurants, too. They exaggerated the threat that Chinese restaurants (considered to be dens of vice for sex, opium, and alcohol) posed to the virtue of white women.

1899 poster showing an armed Chinese man standing over a fallen white woman who represents Western European colonialism

The 1909 murder of Elsie Sigel, a prominent union leader’s daughter, by her Chinese waiter boyfriend in New York City propelled this stereotype further. The press sensationalized the national manhunt. One Connecticut newspaper wrote, “To be a Chinaman these days is to be at least a suspect in the murder of Elsie Sigel.”

A 1910 Chicago Tribune editorial claimed that

“More than 300 Chicago white girls have sacrificed themselves to the influence of chop suey joints during the last year, according to police statistics. Vanity and a desire for showy clothes led to their downfall, it is declared. It was accomplished only after they smoked and drank in the chop suey restaurants and permitted themselves to be hypnotized by the dreamy seductive music that is always on tap.”

1910, Chicago Tribune

Warnings about the danger to white women circulated for many years, leading a flurry of laws which seem silly in hindsight. States and cities enacted or considered legislation to ban white women from working in Chinese restaurants or from patronizing Chinese restaurants.

The idea that the Chinese were both economic and moral threats to white Americans, however, paved the way for passage of the far more harmful Immigration Acts of 1917 and 1924, which broadened the nation’s immigration restrictions to include people from all Asian countries.

Policing

In the absence of legislation, local police departments in cities like New York and Washington, D.C. simply barred young white women from patronizing Chinese restaurants, highlighted by “chop suey raids” in 1918 that targeted numerous Chinese restaurants in New York City. Racial profiling persisted across the country, and police often had discriminatory powers to declare Chinese restaurants a public nuisance.

More regulatory strategies

Other attempts to stamp out Chinese restaurants included laws restricting business activities of non-U.S. citizens and discriminatory application of business licensing and zoning laws against Chinese restaurants.

How Chinese restaurants prevailed

None of the tactics employed over these painful decades prevented Chinese restaurants from continuing to make their mark with the American public. Chinese restaurants, said University of California at Davis law scholar Gabriel “Jack” Chin, “were places of racial mixing, freer from the regulation of a traditional society at a time of cultural change, when women were starting to vote and were headed toward national suffrage.”

In addition, a 1915 federal court decision created a “lo mein loophole” that fueled a Chinese restaurant boom. MIT legal historian Heather Lee explained that once restaurants qualified for “merchant” status, “the number of Chinese restaurants in the U.S. doubles from 1910 to 1920, and doubles again from 1920 to 1930.”

But Chinese restauranteurs continued to face the same discrimination met by Chinese-Americans in all walks of life. A stark example involves famed Chinese restaurateur David Leong. Leong is best known for inventing Springfield, Missouri cashew chicken, the dish which continues to capture the imagination of an entire region to this very day.

At the dawn of the Civil Rights era, Leong planned to open his first Chinese restaurant in Springfield. Though he was financially solvent and a World War II veteran, local banks refused to loan him the necessary money. Only by using a Caucasian friend as a front was he able to get a bank loan. Then, days before the grand opening of Leong’s Tea House in 1963, the restaurant was bombed, an all-too-common segregationist calling card that fateful year.

Today’s climate

Fortunately, the time for such overt discrimination against Chinese Americans has generally passed. Still, Chinese restaurant deliverymen are targeted for robbery and even killed on a more than infrequent basis. Just this year, a horrific episode occurred at Seaport Buffet in Brooklyn. A Russian immigrant claiming that “he was acting out of chivalry by defending Chinese women,” bludgeoned three restaurant workers to death with a hammer, targeting only Asian workers and sparing non-Asian staff.

So maybe the next time you’re at your favorite Chinese restaurant, consider giving the staff there a hug.

Comments

Post a Comment